What a Way to End the Year!

With German Vice Chancellor Robert Habeck at the start-up area of the 5th GABS in Kenya.

“I have a grandfather who still walks straight—that’s because of indigenous foods," a man said to me as he walked past my booth at the 5th German-African Business Summit (GABS) in Kenya this last week, while grabbing a handful of my postcards showcasing indigenous foods.

When I first walked into the posh lobby of the Radisson Blu in Nairobi, my initial thought was: I don’t belong here. Everyone was registering for the summit—shaking hands, dressed in sharp suits, clearly familiar with one another. I didn’t know a single soul. Until two weeks ago, I’d never even heard of the GABS or met the people at the Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung who sponsored my attendance. It all seemed so sudden. But as I stood in my room unpacking, holding the badge with my name and BODY&SOIL printed on it, I realized: none of this is truly random.

My colorful booth at the GABS, showcasing indigenous African foods.

Since 2017, I’ve been deeply immersed in this journey. Through my book, Eating with Africa, and countless personal encounters, I’ve explored what’s happening on the ground in Africa—not just the challenges you read in reports, but the lived realities behind them.

Like the farmer in Sierra Leone with acres of land he couldn’t cultivate due to a lack of manpower, forcing his family to buy food. Or the women in Uganda telling me their harvests decline every year without knowing why. Or the elder in Zambia who had to buy maize from the market because pests ravaged his own crops. I’ll never forget the teenager who knocked on my door last year, asking for €30 for her mother’s type 2 diabetes medication. I gave her the money, but her mother—a woman in her mid-thirties—passed away just days later from a disease that could have been reversed with a healthy diet and lifestyle. Stories like these remind me why I do this work and affirm that I’ve earned my place as a Start-up at GABS!

I may not be a scientist (as people often ask), but I am a nutritionist and I’ve walked the fields, listened to stories, and cooked with over 50 people, hearing the realities firsthand. I'm convinced that to find solutions, you don't need rocket science—you simply need more nutritious, affordable food. There are some striking numbers that confirm this need: Over one billion people across Africa cannot afford a healthy diet, and roughly 30% of children are stunted. Bill Gates recently said regarding Africa:

“The thing that’s holding back potential the most is malnutrition.”

Although I'm skeptical of some of his foundation's approaches, I couldn’t agree more with this statement! But here’s the thing—it’s not because people can’t grow food. Take Uganda, for example; it’s often said to be so fertile that it could feed all of Africa. The issue isn’t a lack of capacity but the one-sided diets heavily based on maize, wheat, and rice.

Even though some types of rice are native to Africa, much of the rice consumed here is imported, along with processed wheat products that are often cheaper than local flours. These imports have become staples, creating the illusion of being “African food.” Maize, for instance, was introduced from South America during colonization. Back then, colonizers dismissed indigenous cereals as inferior, branding them as “poor man’s food.” Sadly, that perception still lingers today.

Ghee from grass-fed cows and indigenous sorghum grain.

Enjoying the traditional grain and clarified butter(ghee), freshly prepared and mixed together, at the home of a Karamojong family in Uganda.

But did you know that Africa has more native cereals than any other continent? Finger Millet, Pearl Millet, Sorghum, Fonio, Tef—these grains are among the most nutritious in the world. Many of these indigenous grains are even drought-resistant. While Europe is going crazy for quinoa, most Africans aren’t aware of their own powerhouse grains.

One story that sticks with me comes from my time researching cultural heritage in Karamoja, Uganda. With a team from the Kara-Tunga Foundation, we explored forgotten cultural foods and crops among the Ik, a marginalized community. We asked them to prepare a traditional dish, which turned into a grand ceremony—complete with goat slaughtering, traditional attire, and even a ritual to read the goat’s intestines to predict the coming harvest and year ahead.

Karamoja, Uganda.

With the Ik community celebrating their New Year’s ceremony by slaughtering a goat and honoring the harvest with indigenous grains.

The Ik predicting the New Year by reading a goat's intestines.

As part of their New Year celebrations, the Ik dress in cultural attire and dance.

Juliana, one of the elders, told me:

“The children call our sorghum ‘poo-poo.”

The IK’s dark-colored, nutrient-rich sorghum has been replaced by white maize and beans, distributed in schools by the World Food Programme. This donor-driven food system not only undermines cultural traditions but perpetuates malnutrition and stunted development. Juliana added that new diseases, such as hypertension, ulcers, and type 2 diabetes, have emerged in the villages over the past 5–10 years, coinciding with the integration of foods from outside into people’s diets.

At the end of the ceremony, we were served stiff sorghum porridge with meat, carefully divided according to custom. Elders savored the intestines, considered a delicacy, while men ate the boiled meat.

In the Ik community of Karamoja, women cook together.

The traditional sorghum stiff porridge of the Ik people in Uganda.

The cultural New Year celebration of the Ik in Uganda.

I’m not saying we need to go back to these exact practices, but there’s enormous potential to adapt and celebrate indigenous foods in a modern Africa. Together with RUCID Organic College, we aim to make grains like sorghum more appealing, adaptable and delicious for today’s modern diets. I already envision BODY&SOIL billboards showcasing these grains, instilling pride and awareness.

Last week, at the German-African Business Summit, my booth in the Start-up area was busy. People—from Africa and Germany alike—were drawn in as I showcased air yams, chayote, and oyster nuts. Most hadn’t heard of them but shared my belief that this must change. These conversations reinforced that we’re just beginning to scratch the surface of Africa’s food potential. One key message from the summit particularly inspired me: Germany is actively investing in African start-ups.

What is the Vision of BODY&SOIL as a Start-up? To reintroduce indigenous foods to farmers' fields and people's plates, while discovering alternatives to one-sided staples that can reach local markets and, eventually, global ones.

The year is coming to an end, and I can’t believe just how much has happened. I’ll spend December cooking and testing indigenous foods (follow my IG channel for that) from regenerative gardens while also renovating BODY&SOIL’s complex at RUCID, funded by the first donations, so that next year we can host experts, learn, and exchange knowledge.

In the meanwhile one of the first steps with BODY&SOIL is assessing what’s already growing at RUCID and determining which plants and crops should be officially tested for their nutritional value. Once we’ve discovered the food jewels that people enjoy eating, and that can potential hit markets, we’ll also explore technologies to reduce food waste through improved storage methods and safer processing solutions.

Did you know food waste emits more greenhouse gases than all air traffic combined?

While this is a future goal requiring more funding, it’s an essential part of the journey.

And regarding funding, this week brought exciting news: the Mirja-Sachs-Stiftung has funded the renovation of our first BODY&SOIL classroom! At the heart of this classroom will be an energy-saving kitchen (I’m currently exploring the possibility of integrating a biogas system), where, alongside community members, we’ll cook, test, and develop what we are growing to discover healthier, tastier alternatives for both children and adults. Additionally, two more energy-saving kitchens for our pilot project in schools have been funded—huge thanks to Marion for organizing this entirely on her own initiative!

If you’d like to get personally involved in helping us bring more nutrition to the soil and onto people’s plates, you can already donate up to €250 without needing a tax receipt. For larger contributions, donation receipts will be issued retroactively once my tax number is finalized. Lastly, I’ve curated a collection of fine art prints showcasing indigenous foods, available on my website. They’re perfect for your kitchen or for breaking the ice with clients in the office – they could also make a nice Christmas gift:)

If we don’t speak before then, I wish you all a Merry Christmas. Enjoy the love and life around you—time flies by so quickly. Thank you to everyone who believes in me, helps me grow inwardly and outwardly, and has made 2024 an unforgettable and power-packed year!

With love from Uganda!

Super proud of my first BODY&SOIL stand!

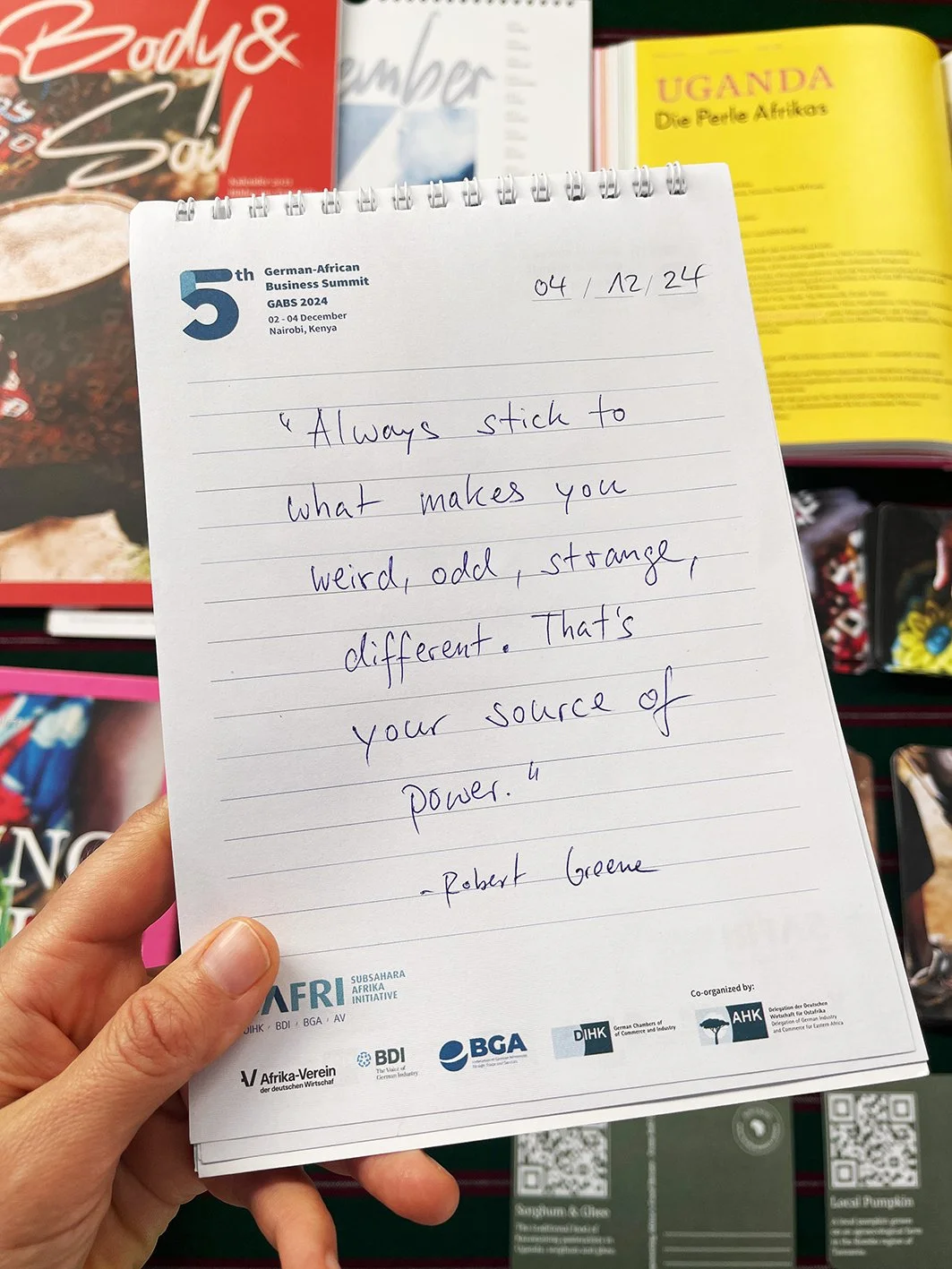

I love inspirational quotes, they keep me going!